When ETH fell below $1,800, Vitalik posted two articles in a row. What was he thinking about?

Reprinted from panewslab

04/01/2025·1MVitalik doesn't care about ETH prices in particular.

Translated by: Golden Finance

When ETH is falling continuously, when many users shout "Fix your eth" under Vitalik's tweets, people are curious, as the founder of Ethereum, what is Vitalik thinking?

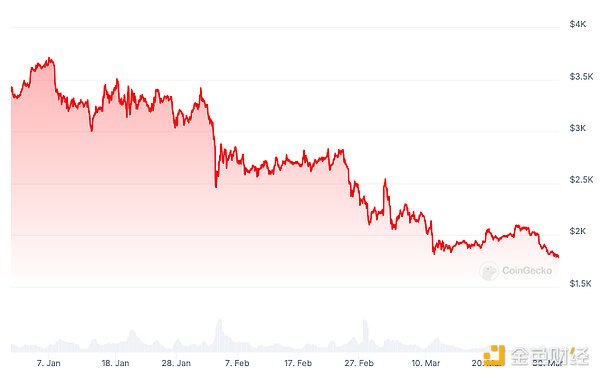

ETH breaks below 1800 USD Source: Coingecko

On March 29, 2025, Vitalik posted 2 blog posts in a row, revealing what he is currently thinking. Obviously, Vitalik doesn't care about ETH prices in particular.

The following are two new blog posts posted by Vitalik recently:

First, the annual ring model of culture and politics

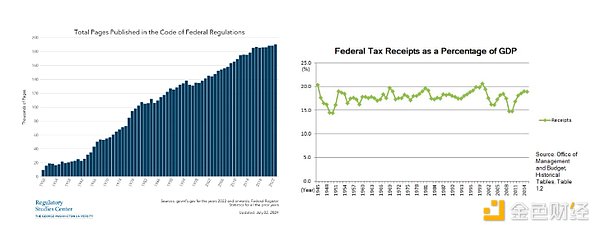

One thing that often puzzles me as I grew up is that people often repeat claims that we live in a "deep neoliberal society" that attaches great importance to "deregulation". I'm confused because while I've seen quite a few people advocate neoliberalism and deregulation, overall the actual situation of government regulation is very different from any regulation that can reflect these values. The total number of federal regulations has been increasing. KYC, copyright, airport security and various other rules are tightening. Since World War II, the percentage of U.S. federal tax revenue as a percentage of GDP has remained roughly the same.

If you tell someone in 2020 that five years later, the United States or China will lead in open source AI and the other will lead in closed source AI and ask them which one will lead where they might be, they might stare at you as if you are asking a tricky question. The United States is a country that attaches importance to openness, and China is a country that attaches importance to closure and control. The United States technology is generally more inclined to open source than China's technology. Please, this is obvious! However, they were completely wrong.

What's going on? In this post, I will propose a simple explanation, what I call the annual ring model of politics and culture:

The model is as follows:

- How a culture treats new things is the product of attitudes and incentives that are popular in a particular period.

- How a culture treats old things is primarily influenced by the prejudice of the status quo.

Each period will add a new annual ring to the tree. As the new annual rings are formed, people's attitude towards new things will also be formed. However, soon, these boundaries will be fixed and difficult to change. New annual rings begin to grow, affecting people's attitude towards the next wave of topics.

We can analyze the above and other situations from the following perspectives:

- There is indeed a trend toward deregulation in the United States, but this trend was most evident in the 1990s (if you look closely, you can actually see this in the chart!). By the 21st century, the tone has shifted to strengthening regulation and control. However, if you look at the specific things that “mature” of the 1990s (such as the Internet), you will find that they are ultimately regulated, based on the dominant principles of the 1990s, which gave the United States (and most of the world due to imitation) decades of relative internet freedom.

- Taxation is subject to budgetary demand, which is mainly determined by the needs of medical and welfare projects. The "red line" in this regard was set 50 years ago.

- Both the law and culture believe that all moderately dangerous activities involving modern technology are more suspicious than activities such as dangerous mountaineering, because dangerous mountaineering has a very high mortality rate. This can be explained by the fact that dangerous mountaineering is something people have been doing for centuries, and when the general risk tolerance is much higher, people's attitudes become firm.

- Social media matured in the 2010s, and culture and politics saw it as part of the internet on the one hand and as a unique thing on the other. Therefore, restrictive attitudes toward social media do not usually persist into the early Internet—and despite the widespread growth of Internet authoritarianism, we have not seen particularly strong attempts to combat unauthorized file sharing.

- Artificial intelligence matured in the 2020s. At this time, the United States was the leading power and China was closely behind. Therefore, it is in China's interests to adopt a "complementary commoditization" strategy in artificial intelligence. This intersects with the general support for open source by many developers. The result is that the environment of open source AI is very real, but is also quite specific to AI; older technology fields remain closed, like walled gardens.

More generally, the meaning here is that it is difficult to change the way a culture treats things that already exist, and the way that attitudes have solidified. It is easier to invent new behavior patterns to go beyond the old ones and strive to maximize our chances of getting good norms. This can be achieved in a number of ways: developing new technologies is one of them, and using (physical or digital) communities on the Internet to experiment with new social norms is another. To me, it’s one of the appeals of crypto spaces: it provides an independent technical and cultural foundation to do new things without being overly burdened by the prejudice of the current status quo. We can bring vitality to the forest by planting and cultivating new trees, rather than planting the same old trees.

Second, we should talk less about public goods funding and more about

open source funding

One topic I have been concerned about for a long time is how to fund public goods. If there is a project that provides value to a million people (and there is no finer way to choose who can get benefits and who can't), but each person only gets a small part of it, then it is very likely that no one will feel that it is in their interest to fund the project, even if the project is generally very valuable. In economics, the language of "public goods" has a century of history. In digital ecosystems, especially in decentralized digital ecosystems, public goods are extremely important: In fact, there are good reasons to show that the average goods that people may want to produce are public goods. Open source software, academic research on encryption and blockchain protocols, open educational resources and more are public goods.

However, the term "public goods" faces major challenges. in particular:

1. The term "public goods" is often used in public discourse to mean "a product produced by the government" even if it is not a public goods in the economic sense. This can cause confusion because it creates the perception that whether a project is a public property does not depend on the project itself and its attributes, but on who is building it and what their claim to be intent.

2. It is generally believed that the lack of rigor in public goods funding operates based on social expectations bias (sounds good, not actually good) and favors insiders who can play social games.

To me, these two questions are related: the term "public goods" is easily influenced by social games, and a large part of the reason is that the definition of "public goods" is easily expanded.

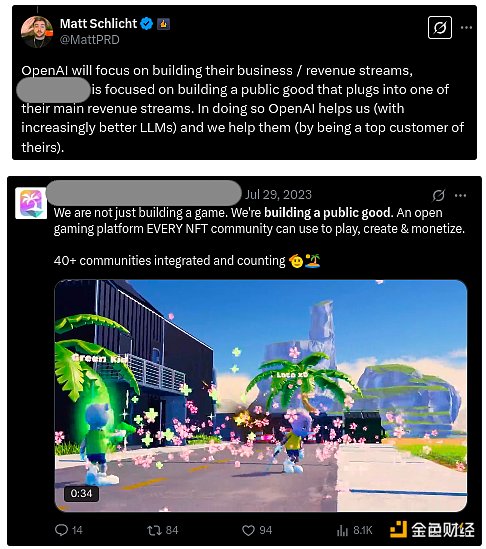

Let's see what happens when searching for the phrase "building the public interest" on Twitter. I've searched now, here are some of the first results:

You can continue scrolling and discover that many projects use "We are building public products" to describe themselves.

This is not to criticize individual projects; I don't know much about both of the above projects, they may be great projects. However, both examples are business projects with their own tokens. There is nothing wrong with becoming a business project, and it is usually nothing wrong with launching your own tokens. However, when so easily downplayed to this point, the term "public goods" now seems to refer to only a "project".

Open source

As an alternative to "public goods", let's think about the word "open source". If you think about some examples of obviously core digital public goods, you will find that they are all open source:

- Research on academic blockchain and cryptographic protocols

- Documents, tutorials...

- Open source software (such as Ethereum client, software library...)

On the other hand, open source projects seem to be public goods by default. You can certainly give a counterexample: If I wrote a software that is highly targeted at my personal workflow and put it on GitHub, then most of the value created by the project might still be my own. However, open source behavior (rather than keeping it confidential) is certainly a public good with very fragmented interests.

One of the real advantages of the term "open source" is that it has a clear and widely recognized definition. Free software definitions for FSF and open source definitions for OSI have been around for decades, and there are natural ways to extend these definitions to other areas outside of software (such as writing, research). In the field of encryption, the inherent state and multiparty nature of applications, and the new centralized vulnerability and control vectors implied by these factors, do mean that we need to expand the definition a little: open standards, internal attack testing described in this article, and walk-away testing can be valuable additions to the FSF + OSI definition.

So what is the difference between "open source" and "public goods"? Well, we can let the robot give a few examples first:

I personally disagree that the first type of example is not public goods. A project has a high bar for contribution that does not prevent it from becoming a public good, as are companies that benefit from the project. Furthermore, an item can definitely be a public item, while the things around it are private items.

The second category is more interesting. First, we should note that these five examples are in physical space, not digital space. So if we want to focus on digital public goods, there is no reason for the above example to object to focus only on "open source". But what if we really want to cover physical goods? Even encrypted spaces have their own passion, hoping to better manage physical things rather than just digital things; in a sense, this is what the network country is all about.

Open source and local physical public goods

Here we can make an observation: While providing these things on a local scale is an "infrastructure building" issue and can be used in an open source or closed source way, the most effective way of providing these things on a global scale often ends up involving…real open source. Clean air is the most obvious example: a lot of research and development has been carried out, most of which are open source to help people around the world enjoy cleaner air. Open source can help make any type of public infrastructure easier to deploy on a global scale. The question of how to effectively provide physical infrastructure on a local scale remains important—but this question also applies to democratically managed communities and companies.

Defense is an interesting case. Here, I want to make the following argument: If you build a project that you are unwilling to open source for defense reasons, then it is very likely that, while it may be a public interest locally, it may not be a public interest globally. Weapon innovation is the most obvious example. Sometimes one side in a war has a stronger moral reason than the other, and it is reasonable to help it conduct offensive actions, but on average, developing technology to improve military capabilities does not improve the world. The exception (defense projects that people want open source) may be the “defense” capabilities that are actually related to defense; one example could be decentralized agriculture, power and internet infrastructure that can help people stay food, function and connect in challenging environments.

So, here, shifting the focus from "public goods" to "open source" also seems to be the best choice. Open source should not mean that "as long as it is open source, building anything is equally noble"; it should be the most valuable thing for humanity to build and open source. However, it is well known that distinguishing which projects are worthy of support and which projects are not worthy of support is the main task of the public goods financing mechanism.